Modernizing a Software Development Team

Outdated systems beget outdated skills

In this blog I write about systems and software primarily from the viewpoint of organizations that are not themselves technology firms. The choice to outsource all software development or to retain a team of developers within an organization’s IT department is a big one. I won’t discuss the timeless “build or buy” decision in this post. Instead, I would like to discuss what an organization does when an in-house software development team has grown outdated. Technology changes fast, and without motivation (at the individual, team, or organizational level) to keep current with new tools and methods, a team of developers can very easily find that their skills are a decade or two behind the times.

Anecdotally, this situation seems to be quite common in non-profit and government organizations. Since these organizations are not driven by profits, improvements to performance and user experience are lower priorities than they are to commercial organizations. Thus, investments in improving software are reduced in size and frequency. If the organization does not prioritize improving the software, the tech stack will become outdated as do the skillsets of the people who are paid to keep that outdated system running.

But what happens when such a team is forced to overhaul an outdated system? Perhaps the underlying tools are insecure and no longer supported. Or perhaps the code has simply become unmaintainable over the years. Can a team whose members have decades-old skills pick up modern tools to build the new system without external help? Will the team require a longer time frame for completion? Will a reduction in scope of the project be necessary to make it realistically achievable? Will the team require extra training resources to modernize their skills? Can the organization tolerate any (or all) of those constraints?

If a consultant must be brought in to help with development the organization will likely (and rightly so) question the ongoing need for the in-house team. It seems that many organizations go through cycles of insourcing and outsourcing technology. Over time the in-house team grows stale and eventually a new IT director decides to reduce in-house resources and go with an external vendor to modernize. Over time this also becomes a problem. Either it is too costly because it is a custom solution for the organization, or it is a generic solution that proves insufficient for the organization’s needs. Either way, a new IT director comes in and recognizes that an in-house team is needed to solve the problem. And so it goes.

Is this cycle OK, or is it something that should be avoided? Technology professionals command high salaries. Therefore, letting go of an entire team, or even a significant chunk of one, can be a quick way to recover a large chunk of an organization’s budget. Outsourcing technology is not exactly cheap either, but there are probably savings to be made. Beyond costs, cutting an in-house team means the loss of a large amount of institutional knowledge. The value of that tacit knowledge can be immense, especially in organizations with large numbers of people, departments, and long-running interdependent systems (e.g. many non-profit and government organizations).

I will not try to argue whether it is better to in-source or out-source. I think it will depend on each organization’s context. However, I will say that if an in-house team already exists, it seems to me in more cases than not that the ideal solution is to keep the team and simply ensure that it does not grow stale. I am sure there are many scenarios where that is not true, but for the sake of argument (and for the sake of the remainder of this blog post) let’s assume that keeping the team is the preferred solution. We are then faced with the following two questions: “how can we modernize an existing software development team?” and “how can we ensure that a software development team’s skills do not grow stale?” A pithy reply might be “build systems that are easy to incrementally upgrade over time so that the technology changes with the times and so do the skills of its maintainers.” Sounds great as a theory, but how do you actually do that in a real life setting?

Case Study: UCLA LIbrary

As it so happens, I am in the middle of modernizing a real life team. In the Fall of 2018 I took on a new position as the Head of Software Development & Library Systems at the UCLA Library. Over the past 18 months, I have initiated several substantial changes to modernize our development processes, tech stacks, and skills.

I. Evaluation

I spent the first few months on the job mostly observing the team and getting up to speed on their current projects and future ambitions. Here is what I found.

1. Structure

- Low team cohesion. The developers were in two different teams without much collaboration between them. The supporting sys admins were on a third team. Thus the software development process was split across three different managers.

- Siloed knowledge. Most of the developers worked on projects as solo developers, not as a team. This gives each system a single point of failure in regards to maintenance and support.

2. Process

- No standard dev process. As solo agents without a standard process, the developers mostly reacted to incoming tickets from stakeholders.

- Unending projects. Without a standard process to define scope, many projects did not have a clear goal for completion and had lingered for years.

- Unrealistic volume of projects. The combination of unending projects with a continual desire to keep doing more new projects meant that the list of active projects grew without bound.

3. Software

- Untenable portfolio of systems. As the aging digital collections system became unable to support the requirements of new projects, a series of boutique systems were created.

- Inconsistent UX. Each system was created by a different developer or vendor, with no central UX process, person, or team to review them.

- Difficult maintenance and deployments. Technical debt reached a level at which it became impossible to update some systems. Deployments for most systems were manual and cumbersome.

- Spotty performance and availability. The older systems experience frequent outages requiring reboots. Others have high latency. Some are all but broken in modern browsers (i.e. Flash).

4. Skills

- Pockets of stagnation. Some of those siloed developers working on aging systems were never asked or given time to build with new tools. Some kept up with modern tools on their own time.

- Widely diverse tool sets. Each system was built by one of an array of siloed developers or another array of independent vendors, each using their preferred tools, leading to a portfolio that goes well beyond the modern trend of “polyglot.”

- Team attrition. Developers for major systems, notably the original digital collections system and the main website CMS, left the team and their positions were filled with developers whose expertise fit newer projects’ needs instead. Thus, the two most important systems are in a state of weak support.

- Outsourced expertise. Many of the systems were built by vendors and handed over to the in-house developers for support.

II. Inspiration

Having diagnosed several symptoms of a team in need of modernization I was faced with the questions posed in the discussion above about what kinds of remedies would be effective for a real-life team. I had done a lot of reading on Agile, DevOps, and UX in my previous job, but had only made minor tweaks to the way that team operated. That organization (The Getty) had undergone a reorganization, and my role as the architect and manager was in a state of limbo. In my new position at UCLA, I came in as the agent of change and I had the authority to set my own vision for the team. This was my chance to implement the ideas I had been learning.

The 5 Pillars

There are countless books, articles, and blogs that give the kind of advice I was seeking. But the five books listed below are the ones I have found to be the most inspiring, insightful, pragmatic, and (most importantly) actionable. They dig to the root of the problems they tackle and give practical advice on how to adopt the philosophies they put forth. I come back to them often for review and reference. These books are the pillars upon which I based the transformation of the team.

About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design (4th ed., 2014)

About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design (4th ed., 2014)

by Alan Cooper, Robert Reimann, David Cronin, and Christopher Noessel There are many great books about user research and interaction/interface design. This is the one that got me hooked on UX as a standard part of the development process. |

The Agile Samurai (2014)

The Agile Samurai (2014)

by Jonathan Rasmusson You can easily get lost in the various flavors of Agile, such as Kanban, Scrum, XP, etc. This book provides a guide to the Agile process that is agnostic about any particular methodology. It gives you just the best practices from across all of the variations of Agile. |

The DevOps Handbook (2016)

The DevOps Handbook (2016)

by Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois, and John Willis This is the most comprehensive assessment of DevOps I have read. The authors do a great job of explaining what DevOps is and isn’t, where it came from, what it offers, why it helps, and how to bring it into your shop. |

Building Evolutionary Architectures (2018)

Building Evolutionary Architectures (2018)

by Neal Ford, Rebecca Parsons, and Patrick Kua Microservices and Event-Driven systems have been covered by many authors before. This group of architects manages to wrap these topics in a nice theory about “evolutionary” systems (those that can be adapted instead of becoming fragile) and offers advice on how to shift your own architectures in this direction. |

Debugging Teams (2016)

Debugging Teams (2016)

by Neal Ford, Rebecca Parsons, and Patrick Kua It’s not all just about process, tools, and architecture. Modernizing a team is also about leadership and management. This book is a concise and practical guide to managing teams, especially those involved in technology development. |

III. Transformation

Taking inspiration from those books, I pushed the following changes to address the issues discovered during the evaluation phase.

1. Strategy

It starts with the big picture view and the question “what do we envision for the future of the UCLA Library’s web presence?” I want a consistent and consolidated user experience. At the moment, we have content stored in multiple repositories, each with their own search interfaces that are not similar in either aesthetics or functionality. Why should users have to search for the right search interface? I envision a single search for all content in the library, even if the content is distributed across a dozen or more backend systems. And when systems or collections necessitate custom interfaces, they should have the same design elements and provide consistent experiences for the users. To achieve those UX and architectural goals, I created a new UX team and a new Architecture team.

-

UX Strategy. Two of the developers on my team were interested in UX. One was more interested in research, the other in design. A perfect complementary pair! I enrolled them both in the UX Certificate program at UCLA Extension. A librarian in another unit had experience with usability testing, analytics, and SEO. I brought the four of us together and formed the UX Team.

In our first year, we assessed the state of UX at the library using a maturity model and put together a 3 year UX Strategic Plan to move us to the next level of that model. This plan includes setting a standard process for all software development that requires UX research and design out the outset of any new development project. We are currently putting this into action by conducting thorough user research ahead of our website redesign.

-

Architectural Strategy. The Architecture Team is made up of the technical leads from each of the software development subteams (described below). We spent most of the first year discussing policies about process and tooling as these underwent significant changes. We are now having more substantive discussions about actual architecture and a development roadmap as we prepare for complete replacements of our CMS and our library catalog and the “sunsetting” of several legacy digital collections platforms.

We aspire to adopt the “evolutionary” architectures mentioned above, such as event-driven and microservices. These architectures are more maintainable and easier to change over time. No more “setting and forgetting” new systems that add to the large portfolio of fragile legacy monoliths. Instead, we hope to continually update an ecosystem of small components and keep pace with the ever changing requirements of the organization and stakeholders.

As we build out our new distributed systems based on these architectural philosophies we will migrate content out of the legacy systems. And we will have a party every time one of those old systems is turned off.

2. Structure

-

Unification. One of the tenets of DevOps culture is that everyone is on the same team with shared objectives. No more division by functional duties or expertise (i.e. Devs vs Ops). No more throwing things “over a wall” for someone else to deal with. Thus, I brought both groups of developers as well as the sys admins that support them into a single Software Development Team, with a single manager (me).

-

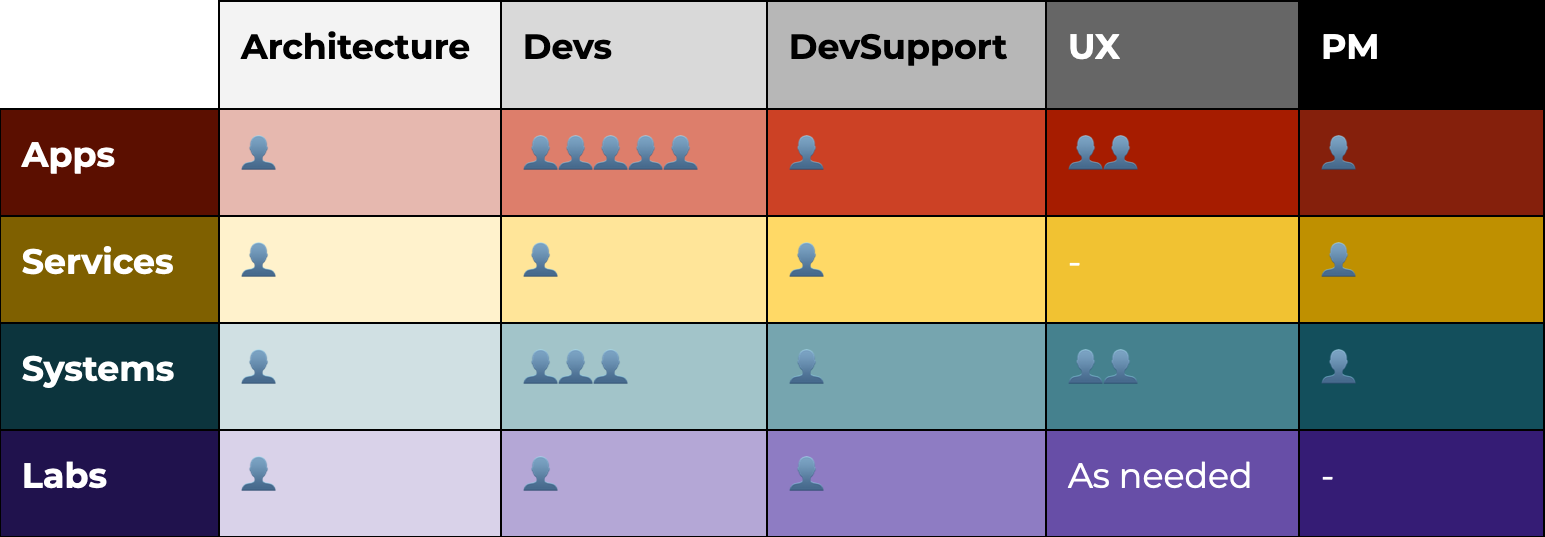

Architectural Subteams. To encourage the shift in our mindset about process and architecture, the team was organized into focused subteams. This move was based on the teaching of Conway’s Law, which states that “any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.” The subteams are:

- Applications Team (discovery, access, and scholarly apps;)

- Services Team (backend APIs; deliver services to the applications)

- Systems Team (vendor systems; middleware; internal business apps)

- The Labs Team (AI/ML experiments)

This organization forces a distinct separation between apps and services, thus avoiding monolithic structures, and encourages cleaner API designs and documentation.

-

The Matrix. Each subteam is cross-functional, with one or more members from the architect’s group, the developers, dev support (sysadmins), project management, and UX when needed. This makes them self-sufficient, a key element of Agile teams as described in The Agile Samurai.

The members of these teams have been shuffled as needed, with one or two people swapping teams at the close of a quarter. The goal is to be flexible but to avoid frequent context switching.

3. Process

The standardization of processes has probably been the biggest and most impactful change the team has adopted. The reorganization certainly changed the culture drastically from one of solo programmers to one based in teamwork. But it has been the adoption of consistent processes for planning our work, contributing code, and deployment that has pushed the team furthest towards being a modern dev team and visibly increasing the quality and quantity of our work.

-

Agile Planning. We have adopted a “non-denominational” set of Agile practices as described in The Agile Samurai. This includes adoption of the usual practices, such as:

- working in two week sprints (each subteam)

- holding daily standup meetings (full team)

- using Kanban boards to visualize our work (each subteam)

- including stakeholders in planning meetings (some subteams)

- conducting retrospectives every sprint (each subteam)

Most professionals that run an Agile development shop will advise you to only work on one project at a time. If you have five projects that each take a month to complete, it is better to work on one at a time and make only one wait five months than to work on all five in parallel and make all customers wait five months.

However, in non-profit’s we do not have the luxury of turning down projects. Thus, we have had to break some rules of Agile to accommodate parallel projects. As discussed in The Agile Samurai the four biggest constraints on a project are time, money, quality, and scope. In non-profits, money is rarely adjusted. If the work is grant-funded, then adjusting time is also difficult. If you want be proud of your work, then you aren’t willing to sacrifice quality either. That leaves scope as the constraint to adjust.

Thus, in addition to sprint planning, I also engage our stakeholders and administrators in quarterly planning. We go over the various projects and requested improvements, prioritize them, estimate the size of each initiative, and reduce the scope of work to a size that is realistically achieveable. This is Agile planning at a macro level. It is something I have been trying to push upwards in the organization to avoid the crushing burden of the always-increasing list of projects.

-

Continuous Delivery. Once the devs were on teams and not working on solo projects we needed to standardize the way code gets contributed, approved, merged, and deployed. The ideal scenario in a modern dev team is Continuous Deployment, in which code that passes automated test suites is automatically merged to the master branch and automatically deployed to production. We opted for intermediate steps in which we strive for Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. Code that passes automated tests is manually reviewed by another developer. If approved and merged it is automatically deployed to a staging environment, but production deployment remains a “push button” operation.

Continuous Deployment requires high confidence in the quality of your team’s code, or an extremely thorough test suite, or an extremely easy process to roll back (or forward fix) production when problems occur. Really, you want all three of those attributes. We have made strides in improving the quality and rigor of our test suites, but we know we still have a long way to go. Therefore, we require that all code is reviewed by a second developer (using pull requests) before merging into master.

I will forbear further discussion of our development practices and deployment pipeline. This topic can easily become just a list of particular tools the team chose for version control, testing and CI, configuration management, containerization, orchestration, hosting, pipeline automation, etc. and this post is about team management, not about tool selection. Suffice it to say we have chosen tools for each of those aspects of the dev process and tried to make our practices standard across all of the subteams. The standardization of the tools and process is the important part, not the particular tool.

4. Culture

The final piece in my attempt to modernize the team was the most nebulous: changing the culture. How do you change the culture of an entire team? In settings with an existing culture or set of policies and norms, I suspect this could be quite a challenge. However, since most of the developers had been working on solo projects, there was not much of an ingrained culture to confront. This it not to say that there was no culture at all. All organizations have a culture. But some are more pronounced than others and some are more rigid than others. In this case, it was neither. It was about as close to a white canvas as one could hope for without building the team from scratch.

Thus, given the opportunity to evangelize a new culture, I faced the question: “what kind of culture do I wish to introduce?” For this, I leaned heavily on the advice of the The DevOps Handbook. In that book, the authors break down DevOps culture into three “ways”.

This first way focuses on making the development process more efficient and improving the feed forward cycles. The second way focuses on improving feed back cycles so that problems are discovered and addressed as soon as possible. The third way focuses on methods of continual improvement of the team and its work through learning and experimentation. These three “ways” are both necessary and sufficient to improve the quality and quantity of work a software development team produces. Thus, I tried to introduce changes that would help us in each of the three ways.

The 1st Way: Efficient Feed Forward Cycles. The changes I introduced here were covered in the sections above. These include:

- Self sufficient teams

- Agile process and planning

- Continuous Delivery

The 2nd Way: Fast Feedback Cycles. Again, the changes I introduced here were already mentioned above, including:

- Automated testing

- Peer reviews of all committed code

- Mini retrospectives every sprint

- Stakeholders in daily standups (solves problems faster than email)

The 3rd Way: Continual Learning, Experimentation, and Improvement. The changes I introduced to address this final “way” are what I wish to focus on, as I have not mentioned any of these changes yet.

-

Refactor Sprints and Goals. It can be difficult to get individual refactor tickets into a sprint. And even when they make it into the sprint, they will often be neglected and buried by higher priority tickets that address existing (and more visible) goals for the sprint or quarter. Therefore, we began dedicating one sprint each quarter entirely to refactor efforts.

Some teams that are struggling to deal with small-community open-source platforms have refactor work that will span more than a single sprint, due to the amount of time needed to conduct an audit and set a strategy for the overhaul. Therefore, instead of a refactor sprint, these teams have a refactor goal for the quarter and during each backlog grooming and sprint planning session we make sure that we make progress towards that goal just like any other goal.

-

Learning Fridays. In order to modernize our skills, the team needs time dedicated to learning new tools and techniques. I began by asking everyone to find time in their own schedules and to dedicate 4 hours a week to learning. I purchased subscriptions to multiple learning platforms for various team members based on their interests and preferred learning methods.

However, just as refactor tickets will be neglected without an agreed upon time dedicated to them, so goes “learning time.” Thus, we designated Fridays as a “no meetings” day and developers are encouraged to spend the entire day on learning and experimentation, though they are free to work on development tickets if they wish. The absence of meetings gives everyone the uninterrupted mental break they need to actually learn new things. We have arranged with our stakeholders to respect the “no meeting” policy. In fact, now other units in the Library are adopting similar practices.

I should note that we do have one meeting on Fridays. We have our 15 minute daily standup at the regular time. But instead of looking at each team’s Kanban board, we look at the “Learning board.” Each quarter every member of the team creates learning goals for themselves and creates tickets for those goals in a dedicated Kanban board. We checkin with everyone during the Friday standup and hear about their progress on their learning topics.

-

Knowledge Sharing Sessions. To spread that learning beyond individuals, we have monthly “Dev Jams” in which team members demonstrate the tools they have been learning or the experiments they have been conducting. This practice existed before I joined the team, but it had languished for a bit. We revived it and have been experimenting with different formats to keep it fresh.

-

Experimentation. Improvement isn’t just about learning new techniques. Not everything that works well for other organizations will be a good fit for ours. Therefore, in conjunction with learning new tools and techniques, we must try things out and determine if they improve our processes or products.

Some of these experiments are conducted by individuals during Learning Fridays, but some are part of the quarterly goals of a subteam. These team experiments are more strategic. They are used to inform decisions about parts of our system architecture or even the viability of entire initiatives. We aim to share that knowledge with our peers via white papers and peer reviewed articles.

-

Quarterly Retrospectives. Finally, I should note that all of the changes I have discussed so far are experiments in themselves. Some have undergone multiple variations to find a form that is beneficial without being cumbersome. One way we continually assess our culture and customs is through a full-team retrospective each quarter. These retrospectives have been very informative and help us focus on what is of greatest concern rather than spending time on matters of interest but not of import. Once we determine what needs to be addressed, we brainstorm ideas and define action items for the following quarter.

Conclusion

It’s been approximately 18 months since I first began initiating changes in the team. As mentioned above, some of these interventions needed more than one variation before gaining traction. I have been incredibly lucky to join a team that was so accepting of these changes. The team members were aware of their needs and welcomed the opportunity to try new tools and techniques and to transform themselves into a modern dev team. We joke sometimes that by purchasing copies of the books mentioned above for several people on my team that I was assigning reading to them as I do the students in my classes. But jokes aside, the team is very much interested in learning and is always happy to get pointers to good resources.

So, the question to ask now is, “did any of these changes help?” I can say with a high level of confidence that yes these changes have improved the quality and quantity of our work and we are now operating like a modern software development team. We still have more to learn and have plenty of room for growth, but we have absolutely leveled up in terms of our DevOps maturity.

Recall the specific issues I observed in the “Evaluation” phase above. Here is a summary of how they have been effectively overcome:

- The reorganization addressed the issues of low team cohesion and siloed knowledge. The teamwork has been truly amazing to watch. Pair programming and mob programming have been adopted by the developers without any push from me.

- Agile planning and quarterly planning have tamed the ever-growing list of unending projects. Stakeholders and administrators are aware that adding to the list of projects or goals means reducing the scope of some or all of them because they are involved in the quarterly planning.

- The new UX Team has begun work on a standard process and a new Design System will be delivered as part of our website redesign project, paving the way for a consistent UX across multiple user interfaces.

- The Architecture Team has pushed standardization, thus addressing the issue of diverse toolsets. They have begun work on a development roadmap that will determine the architecture of our future systems that are easy to maintain and thus address the performance and availability issues.

- There is a fifth subteam I did not mention above, named the Legacy Team. Each quarter this team selects one or more legacy digital collections applications and aims to migrate the content into the new repository and shut down the legacy system, thus reducing our portfolio of supported systems.

- The three preceding measures all address the issues of team attrition and outsourced expertise as we turn off the old systems and build the new systems ourselves.

- The DevOps culture and Learning Fridays have addressed the pockets of stagnating skills.

I considered adding a final section to this post with a quantitative assessment of how effective the changes have been so far. However, this post has already become much longer than anticipated. So, for now, I will conclude with a more qualitative, or anectdotal assessment and I may followup with another post that examines some more quantitative measures. But to be honest, in these matters I feel that a qualitative assessment is more valuable. As a manager I gauge the success of the team not on the count of tickets closed or lines of code written. Achieving our quarterly goals and meeting our stakeholders’ expectations is how we are judged by others, and that is more important than any numbers. Over the past 18 months we have done very well in satisfying stakeholder expectations. Part of that is due to setting reasonable expectation with our quarterly planning, but the bulk of that success comes from the team operating in a way that facilitates high quality and quantity of work.

Success is one thing, but what is more pertinent to this post is gauging the team’s progress. Over the past 18 months I have observed incredible teamwork, increased confidence, improved clarity of direction, proactive problem solving, and an increased desire for continual improvement. I am proud of the work we have accomplished, and I’m not just talking about the software. I’m talking about the culture.

Banner image credit: UCLA Library Digital Collections

Last modified on 2020-05-01